Figure 1

How do old-time languages such as C, Fortran and others survive in a world with Python, Ruby and so on?

There is plenty legacy code still around which need maintaining, of course. And there are (will always be?) a few specific applications where low level is needed. But one of the great things with software is building upon old stuff using new tools, which brings us to our topic today: building a shared library containing some of our C stuff and using it in nice and comfy Python. Figure 1 shows an example of what we can achieve by using graphical tools available in Python to improve our existing code’s text-based output. More on that later on.

For our purposes, we consider shared libraries as a collection of compiled objects condensed into a single file, which may then be called by other software. This is, of course, a simplification. A longer discussion about shared and static libraries can be found in [1].

In this post, we will define a Python wrapper for the linked list data structure we coded a couple of years ago. This is an interesting use case, by the way: writing wrappers for a shared library coded in a lower-level programming language may have several advantages. You could decide to scrap the C code and implement everything from scratch in the higher-level language, but then you’re throwing away precious time spent implementing and testing in the lower-level language. The lower-level library may also offer significantly better performance than a native implementation in the higher-level language. Also, as we will see, writing a wrapper is actually exceedingly simple, as is building the shared library itself.

The process of compiling all our algorithms and data structures into shared libraries was actually didactic, because it enforced some good practices. Our project’s structure is now much more organized and sane; makefiles were written; (many) bugs were found, memory leaks were unveiled and fixed. Overall, our code was improved.

Here’s an example makefile that compiles one of our shared libraries, data_structures:

CFLAGS=-fPIC -DPYLIB

LDFLAGS=-shared -Wl,-soname,data_structures

PYDEP=-I/usr/include/python2.7 -lpython2.7

SRCS:=$(wildcard src/*.c)

../shared/data_structures.so:

gcc $(SRCS) $(LDFLAGS) $(PYDEP) $(CFLAGS) $< -o $@-fPIC stands for position independent code. In short, compiled code will use a global offset table to reference addresses, which allows multiple processes to share the same code. See [2] and [3] for some nice discussions and explanations about PIC and why it is needed in this context. -Wl says that the next option should be passed as an argument to the linker. The option in this case is -soname,data_structures, which defines the shared object’s name (hence soname) as the string “data_structures”.

Now let’s define the Python interface. Let’s start by init.py, where we’ll load the shared libraries:

import ctypes as ct

from pdb import set_trace as bp

libutil = ct.CDLL('shared/utils.so')

libdata = ct.CDLL('shared/data_structures.so')

libsort = ct.CDLL('shared/sorting.so')

__all__ = ['ct', 'bp', 'libutil', 'libdata', 'libsort']ctypes is the native way of loading shared libraries in Python. As the official doc states: “ctypes is a foreign function library for Python. It provides C compatible data types, and allows calling functions in DLLs or shared libraries. It can be used to wrap these libraries in pure Python.”

All functions present in the data_structures library will be available in the Python object libdata. Now here’s the linked list wrapper:

from cdepo import *

def intref(value):

return ct.byref(ct.c_int(value))

class LinkedList():

def __init__(self):

self.ll = libdata.new_list(libutil.compare_integer, ct.sizeof(ct.c_int))

def add(self, value):

libdata.add_ll(self.ll, intref(value))

def add_many(self, values):

for v in values: self.add(v)

def contains(self, value):

return libdata.search_ll(self.ll, intref(value))

def delete(self, value):

libdata.delete_ll(self.ll, intref(value))

def __str__(self):

libdata.print_ll(self.ll)

return ""

def free(self):

libdata.delete_linked_list(self.ll)And here’s a simple test that shows how we can use the Python class which uses our C functions underneath:

from cdepo.data_structures.linked_list import *

print "Creating list"

clist = LinkedList()

print str(clist)

print "Adding 3 and 5"

clist.add(3)

clist.add(5)

print str(clist)

print "Adding 10, 20 and 30"

clist.add_many([10,20,30])

print str(clist)

print "Deleting 5"

clist.delete(5)

print str(clist)

print "Deleting 3 (list head)"

clist.delete(3)

print str(clist)

print "Deleting 30 (list tail)"

clist.delete(30)

print str(clist)

print "Deleting the remaining elements (list should be empty)"

clist.delete(10)

clist.delete(20)

print str(clist)Here’s the output.

In our little example we only used the same functionalities we already had in C. However, one of the great advantages of accessing a library with another language is using tools that are specific to that language. As an example, let’s use Matplotlib to render some images that improve our pathfinding visualization. We built Python wrappers for the necessary functions (Graph-related and Dijkstra’s algorithm) in the same fashion as we did with Linked List. Here’s the resulting script:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from cdepo.data_structures.graph import *

dim = 32

g = matrix_graph(dim)

put_rect(g, 0,3,30,5)

put_rect(g, 2,10,32,13)

put_rect(g, 10,15,12,32)

start = 0

finish = (dim**2)-2

dists = g.pathfind(start, finish)

plt.imshow(g.bgfx_mat(), interpolation='nearest', cmap='Oranges')

plt.show()

plt.imshow(g.dist_mat(dists), interpolation='nearest', cmap='gist_rainbow')

plt.show():————————-:|:————————-:

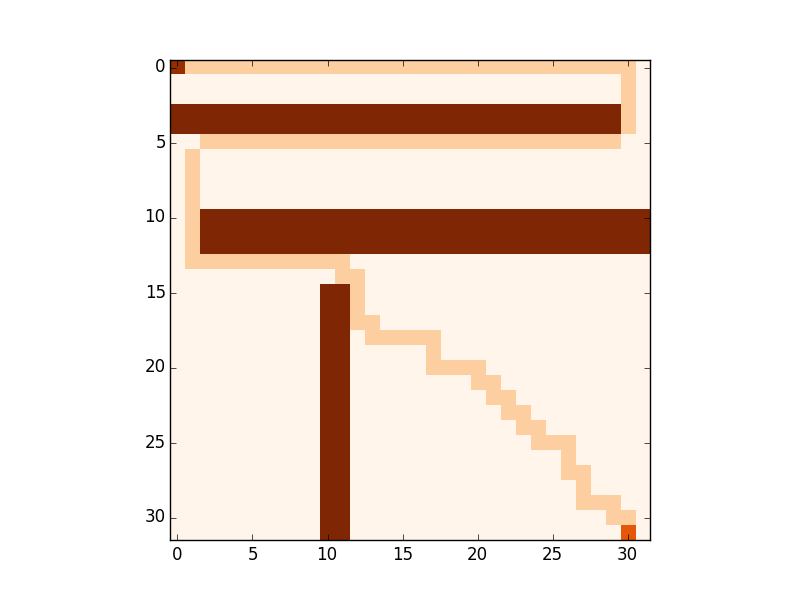

Figure 2

Figure 2’s left picture shows the shortest path (using Dijkstra’s algorithm) between the two highlighted vertices. The brown rectangles represent “walls”, i.e. high-cost vertices. Right picture shows the distances to the starting node of each vertex. Obviously a great improvement over simple text-based output which we use within C (the picture at the beginning of this post illustrates the difference).

Bottom line, compiling your stuff into shared libraries is a great way of reusing code and breathing a whole new life into it.

As always, all the code used in this post is on Github.

Bibliography

[1] Beazley, David M. et al., The inside story on shared libraries and dynamic loading

[2] Position Independent Code and x86-64 libraries

[3] http://stackoverflow.com/questions/7216244/why-is-fpic-absolutely-necessary-on-64-and-not-on-32bit-platforms