What happens when your project’s RDBMS is just not enough to deal with unexpectedly huge amounts of data?

You could try to de-normalize some tables here and there to avoid unnecessary JOINs, create a few indexes, implement some kind of pagination or even pre-process the data into a more palatable format. However, if you did all that and it still was not enough, the “natural impulse” is to give up on the RDBMS altogether and just use Elasticsearch. Sounds like a no-brainer, right?

Well, what if you can’t jump into Elasticsearch right away? This is a more subtle but much more realistic scenario which we faced in a project here at Guava.

In an ideal world, the correct or most appropriate technology stack would be chosen at the very beginning of all projects. For many reasons that are all too familiar to any seasoned developer, this is very seldom the case of any big software. The beginning of the project is precisely when you least know about the software requirements, thus it is often the point when seemingly innocuous choices are made which will cause great pain in the future. Once a wrong or sub-optimal choice is made, it will only get worse over time, even before you even realize it is wrong. While the team is still confident that the solution is salvageable and can be fixed through careful optimizations and esoteric incantations — like we described above — the project is drifting further and further from completion, and a full stop would in fact be more productive.

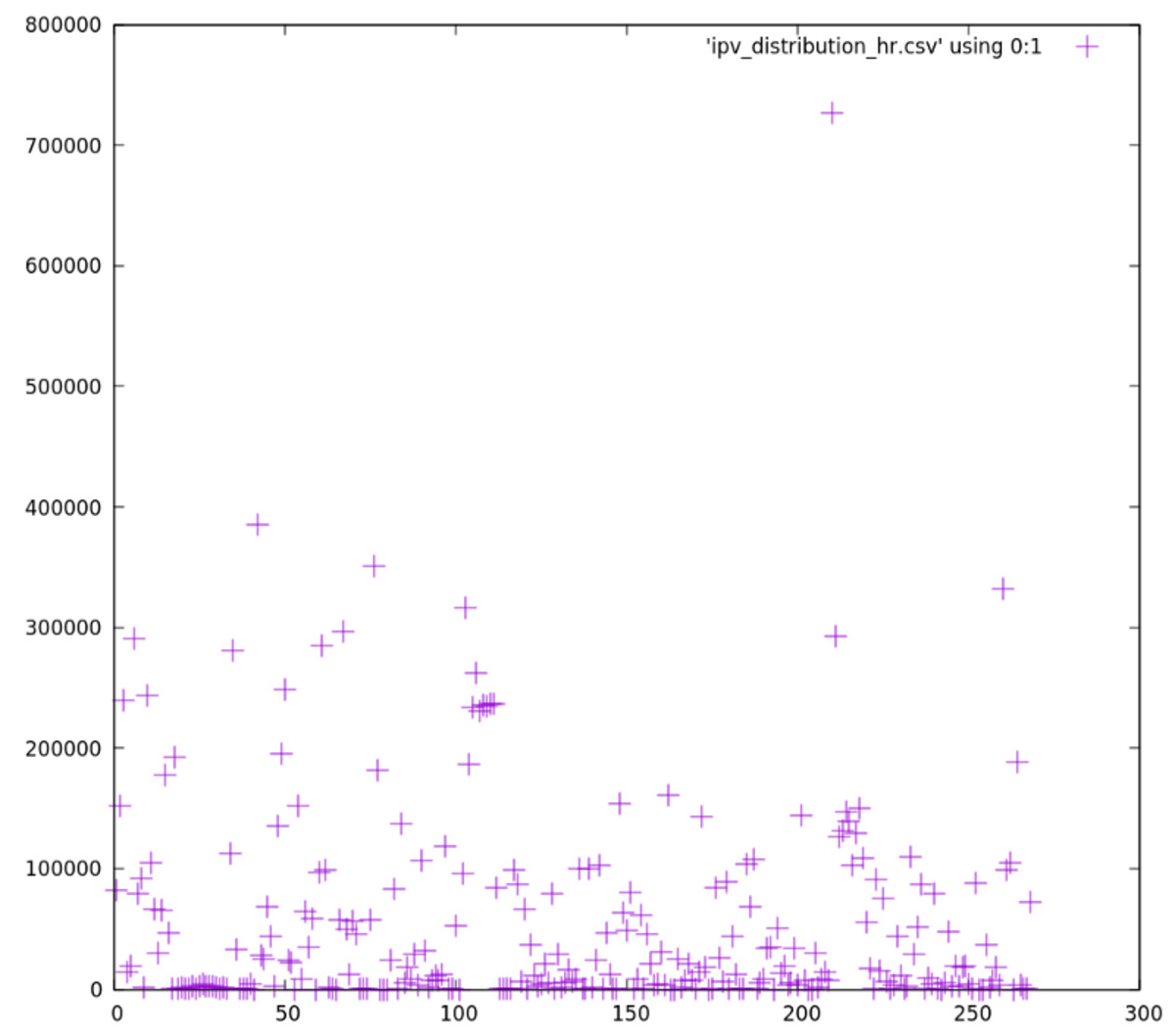

Back to our concrete case: we had a massive and steadily-increasing set of highly normalized data on a RDB. Adding insult to injury, the input data was incredibly sparse, with batch-like data peaks followed by several hours with little activity. The data distribution made it clear that we would have to do some kind of pagination. The following figure shows our input data distribution, where the x-axis units represent 1 hour worth of data, and the y-axis represents the data count in that hour:

As we can see in the chart, many 1-hour blocks had nearly no data at all, and the great majority of blocks had less than 100k entries. A few blocks have a huge amount of data, surpassing 700k entries. This chart has 1-hour precision, but if we zoom in and investigate the same data set with 1-minute precision, the chart would look more or less the same. This is only a small sample of the data set we were dealing with: the full set had over 20M entries, growing at a rate of about 1M entries per month.

We were asked to do some fairly standard BI stuff: report and dashboard generation. Because of the widely normalized data and the sheer amount of rows, we were forced into pre-processing very early in project. Our pre-processing hugely reduced the amount of data that the web app would actually have to process and display to the final user, but introduced a new set of problems: we were effectively de-normalizing the entire data set, which had to be done continuously and in small, manageable chunks (so we could tackle the sparse data distribution), and we were now responsible for maintaining the integrity and completeness of the optimized data. The processing also added a new layer of complexity to the application.

Our solution was viable, but only just; when it came to our attention that the upstream data was actually versioned and non-monotonic, we quickly realized that simply adjusting our solution to deal with versioning would add so much complexity and extra load to the RDB that would render it unusable. The moment had come when we would start feeling the itch to make the jump to Elasticsearch — at least for the optimized, pre-processed layer which we described above, sitting on top of the raw input data. In theory, Elasticsearch would neatly handle all of our major issues: massive data volume, versioning and high normalization.

However, the ideal world and the real world are worlds apart. We had already spent a few months worth of effort in developing and validating an arc of SQL logic that by nature depends on the initial choice of using an RDBMS as data source. Other teams of developers were already working on the same branch. Time constraints made it impossible for us to re-write the whole relational ecosystem, but at the same time continuing to use Postgres on the new layer was definitively not an option due to the versioning and performance issues we were facing.

The right compromise

We made a compromise and decided to use both Postgres and Elasticsearch on the same layer of pre-processed data. This unusual solution allowed us to carry on using most of the valuable relational logic already done, while leveraging Elasticsearch’s speed and document versioning. Sitting beneath the dual-store layer we still had the same sturdy Postgres store with raw data.

The solution can be summarized as follows: Elasticsearch was set up upstream of our project, and an index was created with denormalized data gathered from our most-used tables. On our side, during pre-processing, we queried the Elasticsearch index and dumped the documents in a temporary table that existed only during pre-processing. The rest of the process remained more or less unaltered, allowing us to quickly solve 2 of the 3 major issues we were facing: performance and version treatment. The price to pay was code complexity, the third issue, which increased significantly with this approach. Additionally, this approach nudged the project closer to the ideal solution (using only Elasticsearch in the performance-critical parts of report generation) — other compromises might have gone the other way, digging deeper into RDBMS esotericism and further from the ideal solution.

Our solution was far from ideal: it was a compromise, but it was the most beneficial compromise that could be made at the moment. Sometimes a silver bullet like Elasticsearch seems to exist, but for many reasons it is just out of your reach for the time being and you must settle for a compromise. In these cases, make sure to make the right one.

By Leonardo Brito on May 8, 2017.

Exported from Medium on May 1, 2019.