TLDR A simple metrics-based ranking system is good enough to decide who gets how many resources.

Computational resources – CPU time, memory usage, network traffic etc – are limited. This may be more or less of a problem depending on project/company size and so on; if you’re working on a smaller product with limited traffic, it might not be meaningful at all.

Once past a certain threshold though, expenses with such resources become non-trivial and it begins to make sense to spend some time thinking about how to distribute them as efficiently as possible.

Here’s the problem that got me thinking about this: at work, we had a computational resource that needed to be consumed by a large fleet of workers (think several thousand concurrent), but each type of worker had different productivity, and that productivity changed over time. How can we decide who gets what?

So the problem is: you have a set of consumers that use the same resource, for which you have a static budget. The consumers all solve the same problem, more or less (i.e. have the same output), but come in different types that have different productivities (defined as output per resource consumption). Additionally, although the consumer types solve the same problem, we want consumers to be as diverse as possible – we can’t just pick the best performing one and go with that.

First thought that comes to mind is this seems ordinary enough; there must be an easy, well-known solution. There might be, but I couldn’t find any that was simple and effective for this use case. Closest I got were PID controllers, which solve a similar problem, but probably doesn’t solve the entire problem here (and also seems complicated).

I gave the problem some thought and came up with a reasonable solution that has been working well for a year now.

The problem boils down to two parts:

- Consistently keeping track of productivity among the different consumer types;

- Deciding how to share the resource among the consumers.

The concept that glues both parts is that of the cycle – a repeating time period in which we measure productivity and distribute resources to be shared within that time frame, until the next cycle comes up and everything is recalculated.

Problem 1) boils down to maintaining a time series of how much output per resource each consumer type produced during the latest cycle.

Problem 2) comes almost as a corollary to the former problem: we want the best global output possible, and that can be guessed by using the productivity stats from the previous cycle. This won’t be perfect, because productivity varies over time within each consumer type, but basic statistical intuition says it will be good enough for our purposes.

So the first step of solving 2) is building a ranking of consumers by productivity. We want a diverse set of consumer types, though, so we can’t just pick type #1 and give it 100% of the resources all the time. Also, the ranking might change each cycle, and we don’t want resource distribution to be too volatile – that might become hard to monitor and debug. We want something that is somewhat smooth, stable, convergent, but at the same time that reflects changes in productivity as quickly as possible, and that delivers good global output-per-resource-consumption.

We know that the top tier within the ranking probably deserves more than the the rest, while the bottom tier probably deserves less, and that is the gist of the solution to problem 2). We don’t know beforehand how each consumer will perform though, so it makes sense to start with equal resource distribution among them.

Here’s the complete solution I worked out:

Start the system by sharing an equal amount of resources among all consumers: let’s say every consumer has the same weight W0.

Then, for each cycle:

- Build the productivity-per-consumer-class ranking

- For the top N% consumers, do W += K (limited to a certain maximum)

- For the bottom N% consumers, do W -= K (limited to a certain minimum)

- Translate each W to a real-world resource amount (e.g. “1GB RAM” or something). This involves the weights as well as the global resource budget per time cycle, such that we guarantee we won’t exceed the static budget.

The global sum of weights is kept more or less the same because we’re summing and subtracting the same amounts each cycle (although this isn’t perfect because we have min and max values), so the system is kept fairly stable over time while also reacting quickly to changes in productivity. Also, the system is robust, and blowing up the weights store is no big deal – weights will creep back to their previous values over a short time.

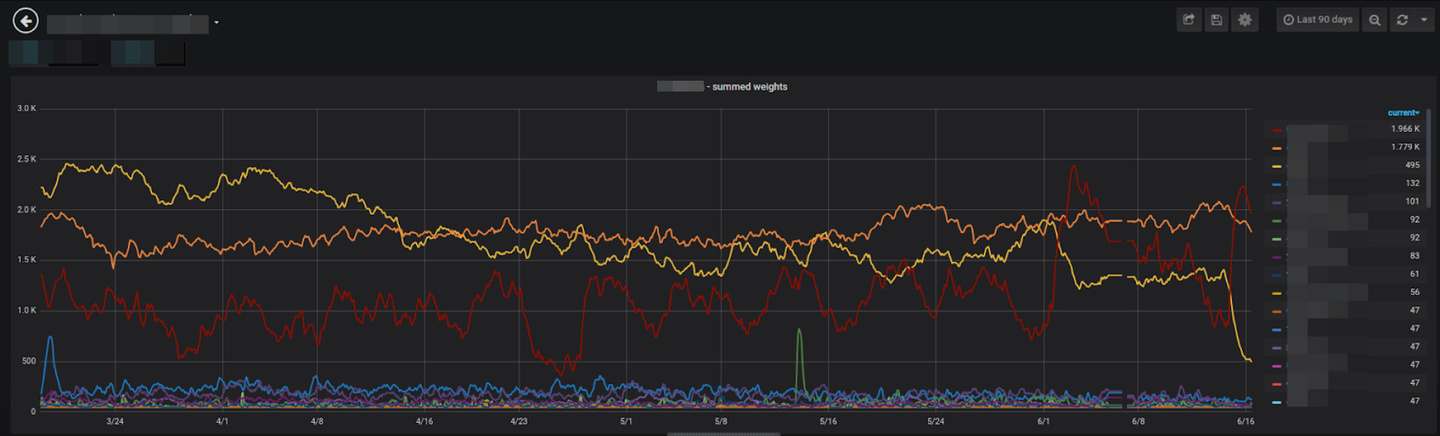

To finalize, here’s a chart showing the weights of different types of consumers over the last few months: